Continuous Insulation Cladding

It Should be Pondered That EIFS is not the Natural “Go-To” Preference to Meet the New Code Requirements, as a Continuous Insulation Exterior Cladding.

A commercial building in Phoenix, at 44th street and Thomas, clad more than 30 years ago with Dryvit Outsulation. It is a beacon of validation to the barrier EIFS performance characteristics; simple sophistication. Image courtesy of Dryvit

A commercial building in Phoenix, at 44th street and Thomas, clad more than 30 years ago with Dryvit Outsulation. It is a beacon of validation to the barrier EIFS performance characteristics; simple sophistication. Image courtesy of Dryvit

“SIMPLICITY IS THE ULTIMATE SOPHISTICATION”

– Leonardo da Vinci

In a previous article it was inferred that not selecting EIFS as the obvious choice was possibly due to its simplicity; it’s just four basic components. Beyond the insulation prowess, it is light weight, a quick install at an affordable cost, universal adaptability and provides ultimate sophistication as an exterior cladding.

The current stucco cladding industry is striving to create insulated claddings that are affordable, will meet the new energy performance mandates, can resist fire, won’t fall off the wall and oh yeah, look acceptable. Those technical minds cogitating to engineering mode, ruminate into the complex; more layers, better drainage, more protective materials, layer upon layers of sophistication … common sense, interrupted.

Please join me in this sojourn as I once again shine the “would-you-look-at-that” light on what I consider to be the simplest high-performance cladding available. But, in order to see the light, we must pass through some darkness, or as I like to refer to it; go down the rabbit hole.

The Number One Choice?

The first consideration of any building cladding is to keep the weather out of the structure. When it was introduced back in the 1960s, a barrier cladding called exterior insulation finish system provided just that. An engineered system of proprietary acrylics and aggregates blended to secret proportions with a smattering of even more proprietary ingredients. All of this placed into a blender, mixed to a spreadable viscosity, a couple of taps with the magic wand, and poof, base coat and finish was born. Applied to an adhered EPS foam insulation layer, the “system” performed just like the EIFS salesforce said it would, simple and fast.

In that first decade or so, a stable of card carrying “certified” applicators applying barrier EIFS in their exclusive areas, helped to make EIFS a very popular cladding. At that time, it was a specialty application of a specialty high performance cladding system installed by specialty applicators. A system whose popularity was bolstered by an energy crunch in the ’70s as an answer to reduce energy consumption.

And like any successful new thing, the increase in popularity of the cladding grew—followed by a rapid growth from only commercial buildings into the residential marketplace. Because of the lightweight characteristics and ease of application, more and more contractors began to apply the EIFS, venturing away from the labor laden stucco three-coat traditional claddings. (Don’t misunderstand my statement—stucco is an excellent cladding, second only to EIFS.)

Popularity begets competition, which took away the “certified” applicators and their exclusive territories, which spawned the “this-is-how-I-learned-to-do-it” teachers and “we’ve-always-done-it-that-way” applicators. Exclusivity cannot maintain its identity when pushed by a progressive building environment. And so, it went that barrier EIFS became the cladding du jour, a popular me too cladding applied by the masses.

I don’t know if it was arrogance or ignorance but “smarter” contractors and their workforces began a degradation of application techniques. Pinning the mesh, omitting caulk joints, going below grade, not back-wrapping and even applying Frankenstein systems (a mixing of non-tested components).

Majority Says

However, there still existed the majority of loyal to their craft applicators, the die-hard installers who never varied from the tested and recommended applications procedures. Those who would never think of buying any component, not a part of the system brand. And, even though barrier EIFS was being tested to its limits by the experimentation and inventive applications of these “smarter” applicators and contractors, it held its own, until it couldn’t.

A good thing happened during this rapid growth of EIFS, the manufacturers re-invested back into the product line and created new products and performance assemblies. It was a calculated step venturing further into engineering performance, and for EIFS meant new textures, air and moisture barriers and drainage. But because barrier EIFS was working so well, no one felt the market would bear an increase in cost for a suggested increase in performance.

Even though the technology was there in the early days, that which would allow the drainage of incidental moisture intrusion, it was to remain dormant until it was to be called upon. And so, it went through the 70’s, 80’S and almost the 90’s barrier EIFS was applied to all types of buildings and was performing as intended, keeping weather out and energy in. It was also during this time that it received the moniker “Ee-fuss” but that’s a battle for another time.

In the early to mid-’90s, the stars aligned to create the perfect storm: One so powerful it almost took out an entire industry. The epicenter; a port city in coastal North Carolina called Wilmington where hurricanes Fran, Emily and Floyd came to party. During that time residential construction was rapidly expanding the luxury housing footprint and people were flocking to buy the beautiful EIFS-clad homes. At those hurricane parties our media correspondents caught wind of an incident, one where moisture had gotten a wood sheathing (not plywood) wet and some mold had begun to form. They began a cacophony of investigative reports pointing to a relatively unknown cladding called EIFS. All asking for your emotional sympathy to the poor homeowners, unwitting recipients of the devil cladding which was being promoted as the cause of mold.

Yes, there was indeed mold present in this very moist climate, but the cause lay in the degradation of EIFS application techniques being used for these fast-paced new builds. The applicators had found the breaking point of EIFS, the point where the barrier alone could not overcome the infiltration of incidental moisture from the perimeters, windows and doors and every other product that touched the beloved EIFS.

Sound Application?

Later in forensic investigations, from those intelligent enough to understand the ramifications of shoddy application, it was discovered that the damage was limited to those areas adjacent to everything that wasn’t EIFS (the interfacings) and didn’t exist in the middle of the field of the cladding. Cries from a competitor cladding product and a charged media began, claiming EIFS was inherently flawed, and tried to oust the cladding through our court system.

But despite the claims, the truth supported by a court of law, was that EIFS did in fact perform as designed and said flaws were application related. This truth, although slow to be recognized, had redeemed the false claims of the performance cladding that is EIFS. As part of a remedial safeguard, two code requirements were born; special inspections are required for all EIFS applications, except when drainage EIFS is used and all structures rated type V (1,2,3,4) must have drainage.

The battle behind them, the EIFS industry dusted off the old engineered drainage systems, added some engineered liquid applied WRBs, invented rough opening flashing products and re-introduced drainage EIFS. (I need to point out that the WRB/rough opening flashing technology create a true continuous water management layer without adding a toolbox worth of components and things.)

Today, when EIFS is specified, it is more often than not, drainage EIFS that is applied. In my southwest region, there is still a fair amount of barrier EIFS applied because it just works out here in the dry heat. By definition, adhesively applied EIFS systems are a true continuous insulating system. And EIF systems comply with NFPA 285, the rigid fire testing for buildings. Let me just point this out one more time; EIFS is one of the most rigorously tested exterior cladding systems there is.

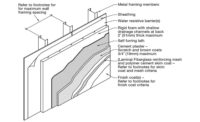

And so, I revisit my first comment, the pondering of the perception that EIFS is not a natural go-to preference for an insulating exterior cladding. Today’s trends are seeking continuous insulation performance in a variety of other claddings. Stucco assemblies with foreign positioning of WRBs, engineered integrations of multi-layered flashings, added layers of sheathings, steel girt components, drainage mats and an insulating layer of foam or rock wool. The answer has been here since the 1960s; energy performance requirements—meet EIFS.

In the next issue, I will explore the stucco CI assembly craze and its comparison to EIFS.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!