Preserving the Entrepreneurial Spirit

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLYER/ATLANTA. (www.hillyerphoto.com)

A beautiful 19th century Italianate farmhouse has in many ways become a true historic preservation project. One of 18 historic structures on 173 acres of land situated just outside the North Georgia mountain town of Helen, Hardman Farm was owned in the early 20th century by physician, entrepreneur, farmer and former Georgia Governor Lamartine G. Hardman, who used the property as a summer retreat and for experimental farming techniques.

According to Susan Turner of Lord, Aeck & Sargent’s Historic Preservation Studio and the project’s principal in charge, the house is a unique historic resource that required a unique approach to its preservation. While most historic buildings are modified over time to keep up with changing tastes and technologies, Hardman Farm remained relatively unchanged over its 140-year history. The house still retains its 1870’s interior finishes, original gas lighting fixtures (modified only minimally for partial electrification in the early 20th century), and original and early 20th century plumbing fixtures. Research indicated that the most significant period of occupation was approximately 1915 to 1925, so this was the timeframe selected as the period of interpretation for the house restoration.

“Today,” Turner says, “the house stands as a sort of time capsule providing a rare authentic glimpse into the architecture and technology of the late 1800s and early 1900s. For this reason, the project team used an approach of conservation: gently cleaning and renewing historic materials and features. All efforts were made to minimize the impact of the team’s work on the historic materials and spaces. This philosophy of touching gently and leaving no trace applied to every aspect of the project — from the team’s approach to sustainable design to materials conservation.”

CFD and Energy Modeling

The team of Garbutt Construction, which served as design-builder, and architecture firm Lord, Aeck & Sargent partnered with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to restore the farmhouse for $2.1 million. The DNR challenged the design-build team to complete a historic restoration project that would incorporate principles of sustainability and retain as much of the existing farmhouse structure as possible.

“Some preservationists don’t believe that historic restoration can be accomplished sustainably, but the Hardman Farm house restoration demonstrates that historic restoration and green building principles go hand in hand and actually complement one another,” says David Freedman, who served as the DNR’s project manager on the restoration. Freedman, who is now retired from the DNR and puts his expertise to use providing green building strategies and training to A/E/C professionals and building owners, also notes that most historic structures were built sustainably to begin with. The house at Hardman Farm, he says, is no exception.

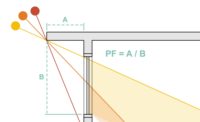

For example, the house is oriented on the site so as to minimize solar gain, and its wraparound porch, deep overhangs and operable shutters help keep it cool in the summer. The house itself features stack-effect ventilation, a form of natural ventilation in which air is drawn up vertically through the two-story house, its attic and out through the cupola on the roof.

“We were originally looking at this project as we would the restoration of a historic home into a house museum. As such, our intent was to add a mechanical system for air conditioning and heating,” Turner says.

“We worked with EMC Engineers, which constructed a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model to study the influence of outside temperature on the interior of the house,” he adds. “We were surprised to learn from the model that there were very few hours where the temperature inside the house exceeded 80 degrees, and then only late in the day, when the sun strikes the west walls.

“As a result the DNR decided to condition the house with its original natural ventilation strategies, as their primary concern was for the house to remain as true as possible to the historic character of the selected period of interpretation,” Turner says. “The house was designed to function in those conditions, and the furniture, which was given to the DNR by Dr. Hardman’s descendants, had already adapted to the thermal conditions. So we switched our approach from one of restoration and adaptive reuse to one of preserving the original thermal environment.”

After the CFD model was completed, the Lord, Aeck & Sargent design team conducted energy modeling and life-cycle costing to determine the best option for achieving thermal comfort in the chilly North Georgia mountain winters.

The National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, a research division of the National Park Service, in July awarded the DNR an $11,000 grant to collect data at Hardman Farm in order to monitor building energy performance in comparison to the energy model.

“Our goals were to minimize the impact of installing a heating system on the historic character of the house without sacrificing operating efficiency,” says Julie Arnold, project architect at Lord, Aeck & Sargent. “We achieved both goals by selecting an underfloor hydronic radiant heating system to heat only the first floor, allowing heat from the system to maintain an acceptable second-floor temperature, even in the coldest weather.”

In keeping with the history of early adoption of technologies like indoor plumbing and electricity by the first owners, the team selected an unobtrusive but sunny area near the farmhouse for the installation of 22 solar panels surrounded by a picket fence. The renewable energy solution is a 3.2-kilowatt grid-tied system in which the power generated will offset much of the electricity used by the main house.

Interior Finishes Restored with a Minimalist Approach

Just as the design team used a minimalist approach for achieving thermal comfort, finishes analyst Welsh Color & Conservation and a team of paint and plaster conservators from The Magic Brush and Architectural Conservation Services, respectively, devised a conservation approach for the interior finishes.

The finishes team determined that the house’s interior wood trim, covered with layers of dirt, still retained the original white painted finish. Concerned about cleaning the painted surfaces while also leaving some patina appropriate for the age of the structure and without damaging the finish, the team tested various products and combinations of products. Through a process of elimination and application testing, it was decided to use a diluted citrus cleaning solution.

The plaster wall and ceiling surfaces were not originally painted but were coated during the early years of the house with calcimine, a glue-based paint commonly used in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The team found remnants of calcimine on the walls behind large pieces of furniture and believes that the previous occupants had cleaned off the calcimine without moving the furniture. It was decided to maintain the uncoated state of the plaster walls and ceilings, leaving the remnants of calcimine untouched.

The plaster contained numerous cracks that needed repair, and this process was complicated since the repairs would not be covered by a new paint finish. “While the standard technique for repairing plaster involves widening and then filling the cracks, the team elected a minimalist process in which the cracks were delicately infilled,” Turner says. She adds, however, that there were some portions of the cast plaster cornices that required replacement due to water damage.

Electricity Replaces Gas Lighting

According to Turner, the restoration began with a conditions assessment of the farmhouse, kitchen and a breezeway that attaches the two.

“We believe that the house was used by Dr. Hardman and one of its two previous owners primarily as a summer retreat, and because throughout most of its history it wasn’t used year-round, we found it to be amazingly intact and in reasonably good condition,” Turner says.

Nevertheless, much work was required to restore the 5,160-square-foot house to its period of interpretation and make it code-compliant.

For example, although the house was built with gas lighting, Hardman introduced minimal electricity in the early 20th century. Some of the original gaslight fixtures had been electrified, and while electrical outlets were installed in the baseboards there were no wall switches. Since these components of early electrical systems were present in the house during the period of interpretation, the design-build team determined that it was appropriate to retain the visible portions of these systems. The team sent the original gasoliers to a specialty lighting restoration company for rewiring to bring them up to code, and to also have their original metallic gold paint finish conserved.

A small viewing panel was installed in one of the second-story bedroom floors to help visitors visualize the evolution of the three generations of lighting systems. Here, visitors can see 1870’s gas piping, an early 1900’s knob and tube system to electrify and modify the gas lights, and the current code-compliant wiring.

Meeting Challenges

“Because the house was so unique in how little it had been changed over the years, we thought that it was very important to only make absolutely necessary changes during the restoration,” states Turner. “This need for restraint played out in all aspects of the project.”

She cites the mechanical system as a key example. “Since the house had never been altered to add systems, we were very concerned about the array of implications that systems could have, including their effect on historic materials and the physical implications of installing ductwork and equipment. This concern, of course coupled with the desire to be as energy efficient as possible, led to the analysis to understand the passively cooled environment and the detailed comparative analysis of heating systems and ultimately led to the decision to not install mechanical cooling and only install underfloor heating at the first floor.

“Another example of the need for restraint was the finishes conservation, where processes for cleaning and conserving the finishes were devised through a series of mock-ups executed by highly skilled conservators,” she adds. “Each mock-up was guided by the goal of doing no more than absolutely necessary to clean and stabilize the materials. In almost every instance it would have been easier for everyone on the design and construction team to use more conventional approaches, but this house deserved a more careful and gentle approach.”

While not yet open to the public at the time of publication, Hardman Farm will become the next State Historic Site and be a showcase for the past as well as sustainable and preservation practices of the present.

HARDMAN FARM

Type of Project: Renovation

(Historic Preservation)

Location: Helen, Ga.

Size: 5,160 square feet (house)

Cost: $2.1 million (U.S.)

Certification: LEED Gold

Restoration and Adaptive Reuse Activities

Work to the farmhouse, kitchen and breezeway included:

- Exterior woodwork restoration, especially of the porch columns and roof overhangs;

- Repainting of the house exterior — which Welsh’s analysis showed had been painted many times — to match the original white, along with repainting of the porch floor to a reddish brown and porch ceiling to white. The edge of the porch ceiling included a detailed trim of cast plaster mini crown molding, which was repaired before the repainting. The window shutters and screen frames were repainted to match their respective dark green and black;

- Replacement of four broken sidelights surrounding the main door. The sidelights, ruby red with flower etched details, were copied to look like the originals;

- Complete restoration of the windows, including sash removal/restoration, replacement of the muntins, which had been eaten by squirrels, refurbishment of the original wood, and protection of the interior paint finish;

- Repainting the heart pine floors in two rooms, and removal of floor paint in another room where it was determined that painting had taken place after the period of interpretation;

- Cleaning of the clear finished mahogany interior doors, and inpainting of the grain painted heart pine interior doors and eight marble painted slate mantels;

- Restoration of the historic hardware, including the ornate hardware on the main door, the knob and skeleton key locks on the bedroom and parlor doors, the black cast iron surface mounted rim locks on the doors, and the original door hinges;

- Removal of a 1950s-’60s room addition near the butler’s pantry at the back of the house;

- Conversion of the butler’s pantry, which had been altered after the period of interpretation, into an ADA-accessible bathroom;

- Addition of an underground, 1,700-gallon cistern to collect rainwater from the farmhouse roof. The water is used for landscape irrigation;

- Cleaning of the 360-square-foot kitchen, which was otherwise in good condition;

- Addition of a wheelchair lift onto the breezeway for ADA code compliance; and

- Redecking the breezeway and bulking up its framing. The breezeway had at some point been replaced with southern yellow pine and was not in good condition.

Project team

Owner: Georgia Department of Natural Resources (Atlanta)

Design-Builder: Garbutt Construction Inc. (Dublin, Ga.)

Architect: Lord, Aeck & Sargent (Atlanta office)

MEP/FP Engineer and CFD Modeling: EMC Engineers (Alpharetta, Ga.)

Structural Engineer: Willett Engineering Co. (Tucker, Ga.)

Civil Engineer: Eberly & Associates (Atlanta)

Finishes Analyst: Welsh Color & Conservation (Bryn Mawr, Penn.)

Paint Conservation Consultant: The Magic Brush (Greensboro, N.C.)

Plaster Conservation Consultant: Architectural Conservation Services (Manchester by the Sea, Mass.)

Surveying Services: LandAir Surveying Co. (Roswell, Ga.)

LEED Administration: Freedman Engineering Group (Marietta, Ga.)

Materials

Exterior Products

- Radiant Floor System: Watts Radiant, Lochinvar Circulating Pump, Hydronex Boiler Panel, Onix Tubing, Tekmar Wall Sensors

- Solar Panels: Radiance Solar, 3-kW ground-mounted Suniva Module Array with a SMA Sunny Boy inverter

- Cistern: Rain Harvest Company, Leader Rainwater Pump, Snyder 1700 Fallon Cistern

- Path Paving: Slatescape

- Exterior Painting: PPG Industries

- Exterior Plaster Trim Repairs: Matrix Neo

- Wood Siding and Porch Repairs: Abatron Liquid Wood and WoodEpox

- Wheelchair Lift: Garaventa

Interior Products

- Interior Touch-up Painting: Benjamin Moore

- Accessible Bathroom Fixtures: Kohler Highline Pressure Light 1.0 Toilet, Kohler Pinoir Wall Mounted Lavatory, Kohler Waterless Urinal

- Plaster Restoration Products: Ivory Finish Lime, USG Moulding Plaster, Rhoplex MC-76, Rhoplex 1950, Acrysol WS-24

- Plaster and Painted Surface Cleaner: Simple Green

- Wood Paneling and Door Touch-up Coating: Zinsser Shellac

In addition to LEED Gold, the farmhouse has received the Marguerite Williams Award, which is the Trust’s highest award, and an Excellence in Restoration Award from the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation. IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLER/ATLANTA.

The project also was CHOSEN AS AN AIA Atlanta COTE (Committee on the Environment) Showcase Winner at the 2011 Greenprints Conference. IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLER/ATLANTA.

Oil-based paints often gave way to calcimine so builders and homeowners could “finish” their projects more quickly. IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLER/ATLANTA.

Calcimine was also often used because it could quickly and inexpensively cover soot-stained walls and ceilings. IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLER/ATLANTA.

The Georgia DNR purchased Harman Farms from Hardman family members in 2002. IMAGES © JONATHAN HILLER/ATLANTA.

In addition to the farmhouse, an old dairy barn and gazebo already have been restored, and the DNR plans to eventually restore all buildings on the historic property.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!